Optimizing L-Systems

Socially isolating through obsessive micro-optimization.

Overview

This week in class I gave a lecture and live-coding demonstration about L-Systems, which sent me down a deep rabbit hole of optimization. My goal was to produce the absolute fastest L-System renderer possible, in terms of seconds per line segment computed.

Boundaries are important, so to prevent myself from going too bonkers, I set a few for myself:

- no explicit SIMD assembly or intrinsics (SSE/AVX/etc.)

- no messin’ around with CUDA, OpenCL, compute shaders, or other GPU nonsense

- no LLVM or generating machine code at runtime

Even working within these very reasonable boundaries, I was nevertheless able to obtain more than a 1200x speedup over my initial Python program.

As usual, code to accompany this blog post is up on github and you can also jump down to the results section to see the hard numbers.

Background: introduction to L-Systems

Note: If you’re already familiar with L-Systems you can just skip to the Implementation section below.

L-Systems, or Lindenmayer systems, can generate beautiful organic-looking and fractal patterns by successively applying a set of string replacement rules, starting from an initial axiom string. The symbols that comprise these strings are interpreted as turtle graphics commands that draw a line segment along the current rotation angle, increment or decrement the current rotation angle by a constant, or save/restore the graphics state.

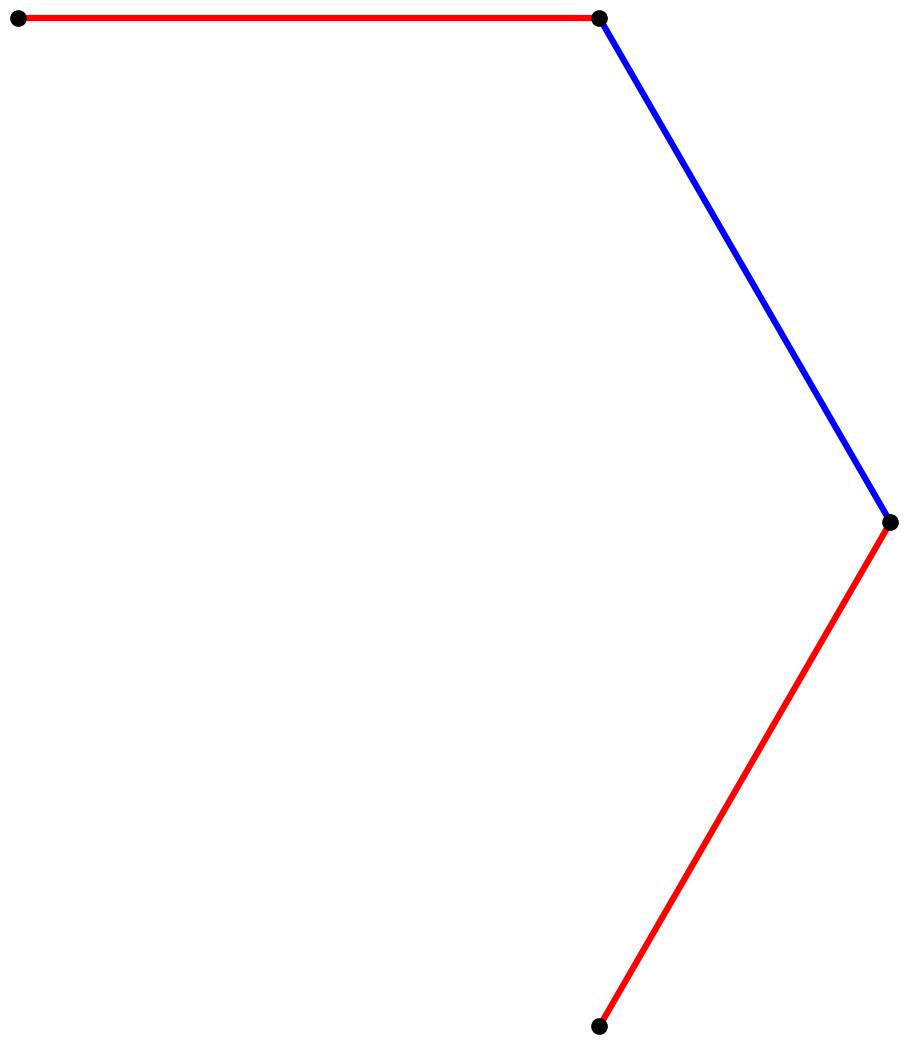

For example, consider the Sierpinski arrowhead L-System with axiom

A, angle increment 60°, and replacement rules:

A→B-A-BB→A+B+A

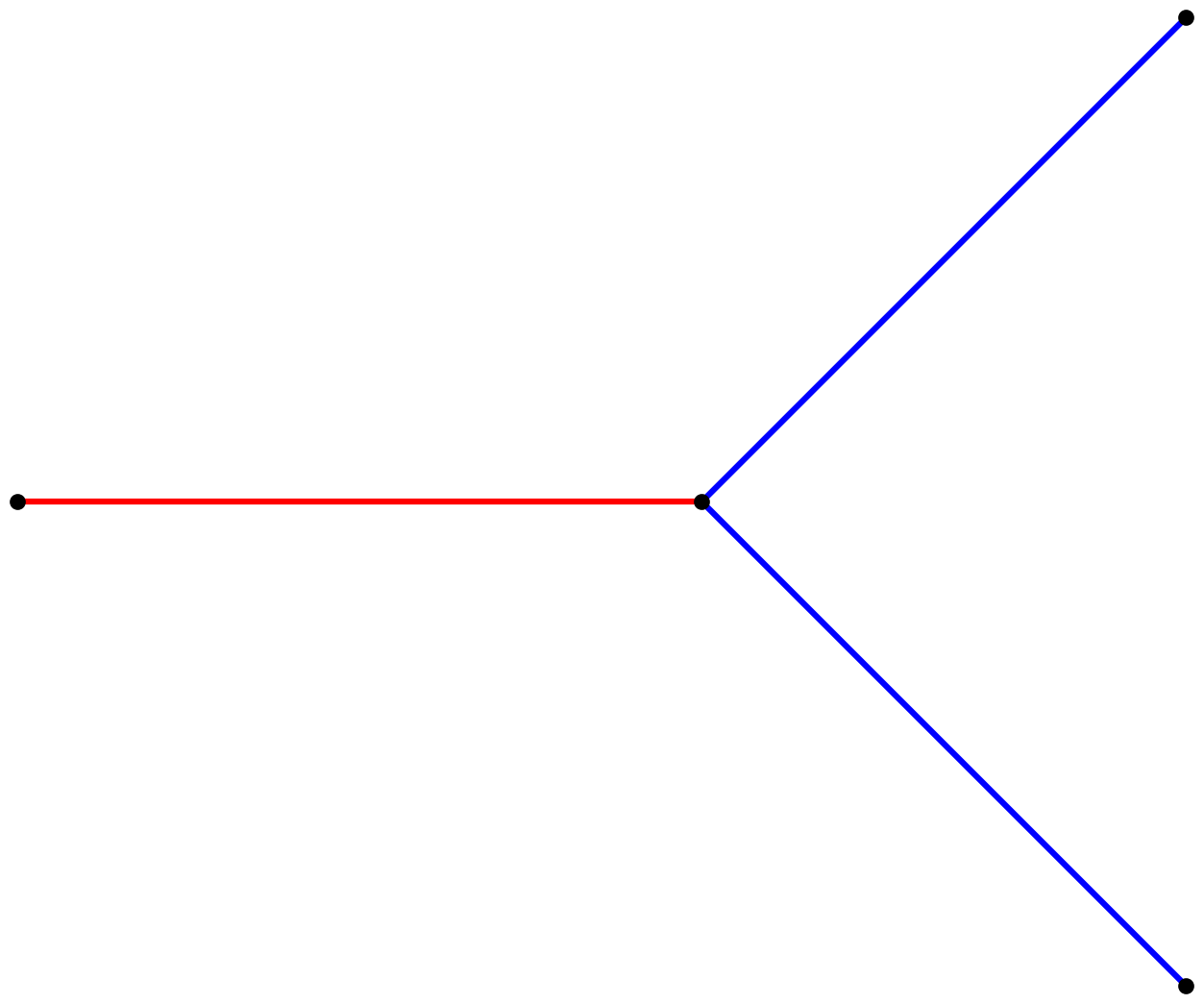

Iteration zero of this L-System consists of the string A, which

draws a single line segment. To clearly illustrate the effect of

string replacements, we will give each line drawing symbol its own

color, so A gets the color blue, as shown here:

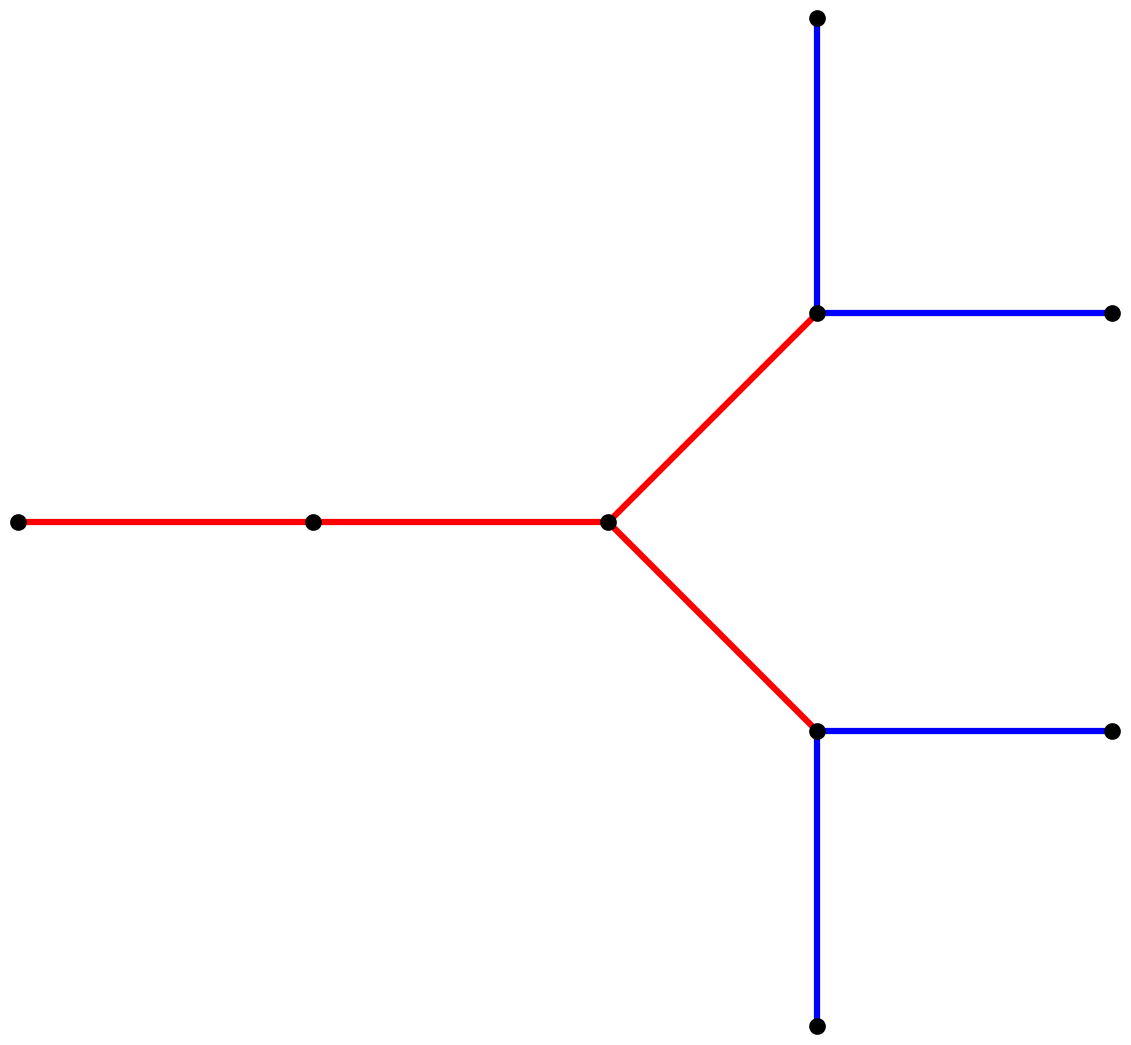

In iteration one, we invoke the first rule to replace the single A

with the string B-A-B, which consists of a B segment illustrated

in red, a right turn by 60°, an A segment (blue), another right

turn, and a final B segment (red). It produces this output, starting from the upper-left dot:

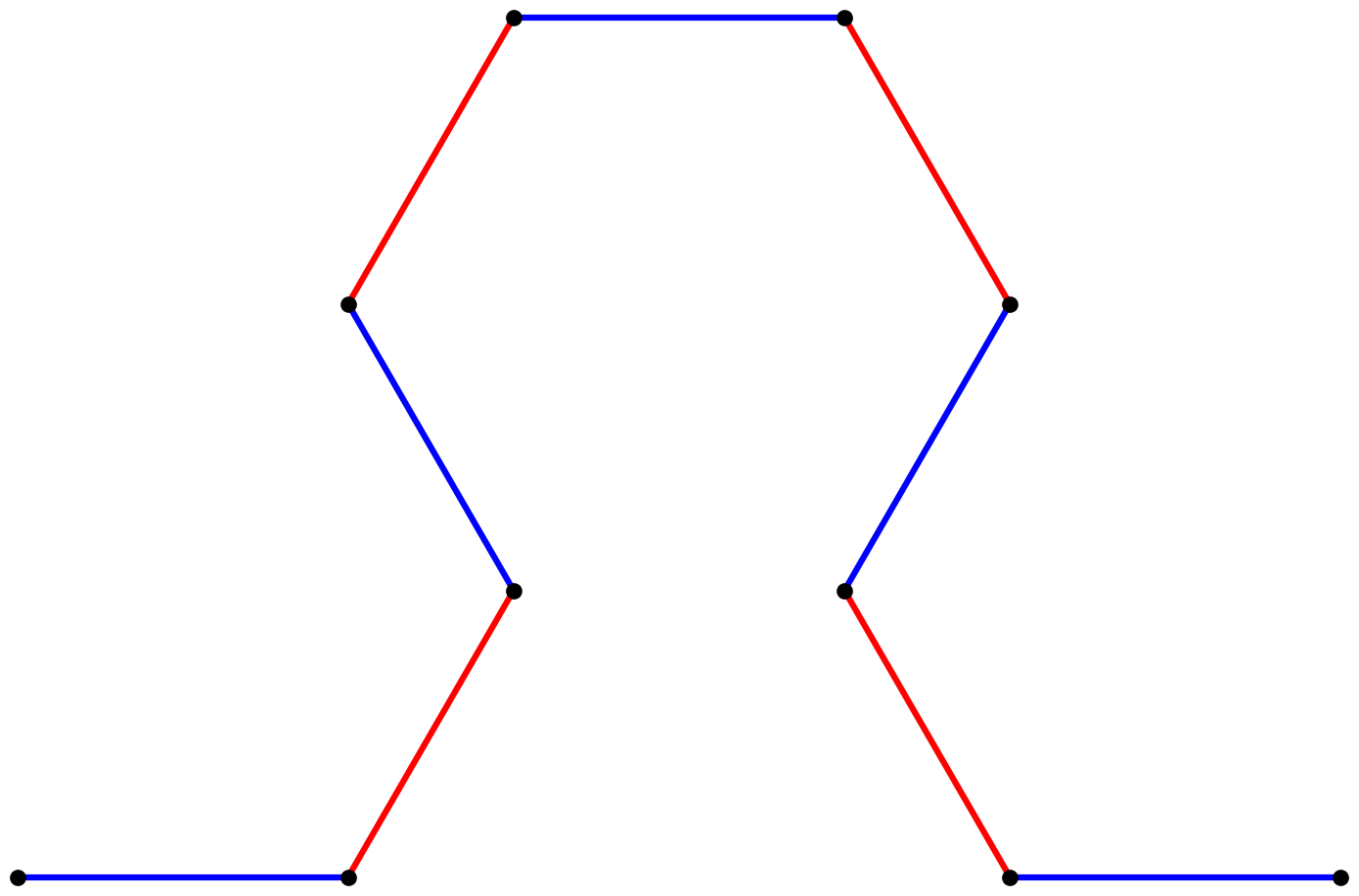

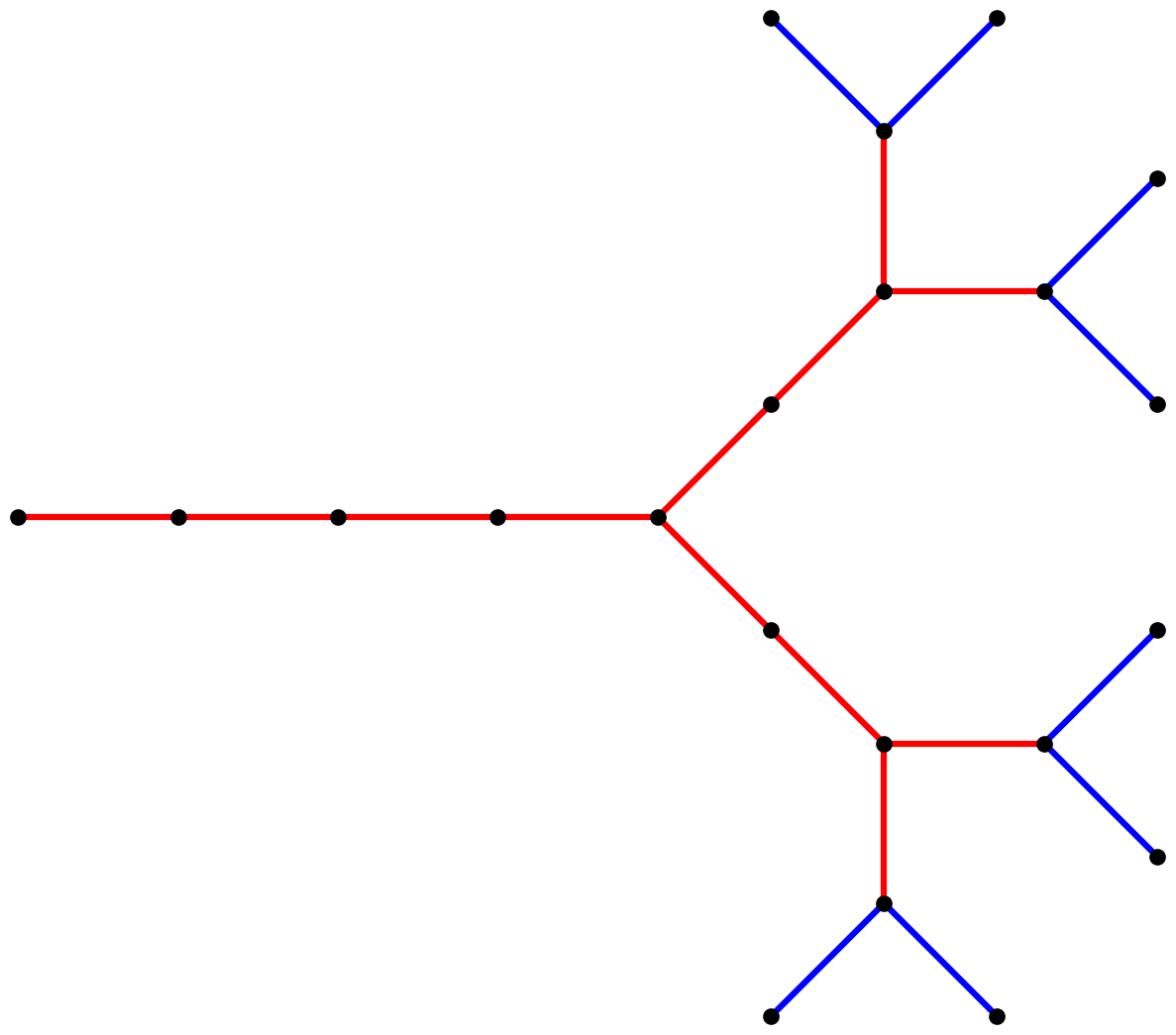

To obtain iteration two, we re-apply the replacement rules to the

iteration one output. The resulting string is A+B+A-B-A-B-A+B+A, and it

produces the graphical output (again starting from the left):

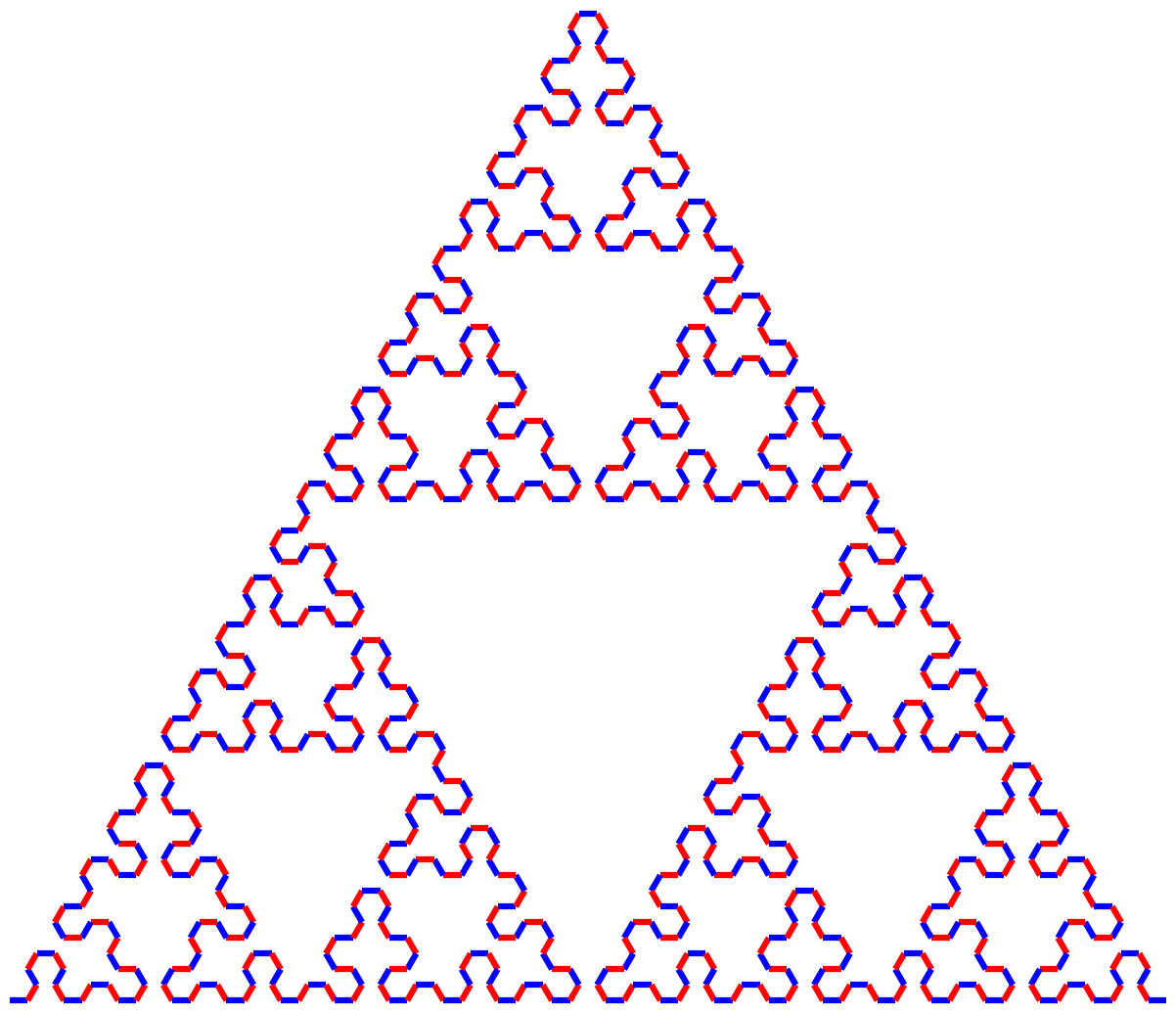

Note that each + symbol above corresponds to a left turn, as opposed

to the - symbols which correspond to right turns. If we let this run

to iteration six, we see a familiar fractal pattern emerge.

The graphics state stack

The example above illustrates drawing segments and turning, but

there’s one more pair of symbols our L-System renderer needs to

handle. The stack push symbol

[ saves the current turtle graphics state (both position and orientation), and the stack pop symbol ]

restores the last previously saved state.

To illustrate this, let’s consider the simple tree L-System with axiom

F, angle increment 45°, and replacement rules:

F→X[+F][-F]X→XX

Iteration one of this system produces the string X[+F][-F].

Let’s interpret it one symbol at a time:

Xdraw a red segment[save the current graphics state+turn leftFdraw a blue segment]restore the graphics state to where it was after step 1[save the graphics state again-turn rightFdraw a blue segment]restore the graphics state again

Here’s the graphical output of iteration one:

Iteration two produces the string XX[+X[+F][-F]][-X[+F][-F]]. Each

branch from iteration one is now an entire iteration-one tree. Also,

the “trunk” has grown twice as long. Here’s what it looks like:

In iteration three, we again replace each red segment with two red segments, and replace each blue segment with a “mini-tree”:

Hopefully by now you’re starting to understand how L-Systems turn strings of symbols into pictures. For additional examples of L-Systems and replacement rules, see the appendix below. Also note that in general, L-System renderers do not color their graphical output by symbol, so most renderers would have produced all of the output above in a single color and without the little dots to delineate the extent of each segment.

Implementation

The job of an L-System renderer is to take a description of an L-System (axiom, angle increment, and replacement rules) along with an iteration count, and produce a list of line segments to draw. I want to be very clear that I’m not at all focused on fast drawing of line segments – instead, my goal is to compute the \((x_0, y_0, x_1, y_1)\) coordinates for all of the line segments as quickly as possible for a given L-System and iteration count.

Therefore, the metric for benchmarking is unit time per line segment computed (lower is better).

In fact, drawing is disabled when benchmarking, and is enabled only to verify line segment output for correctness. To actually produce graphical output, we feed the line segments output by each program to a matplotlib.collections.LineCollection object for plotting.

v0: Initial version

The program

lsystems_v0.py

is very close to what I live-coded during my class demonstration. At

its heart are two functions lsys_build_string and

lsys_segments_from_string. The former is responsible for applying

repeated string replacement to the initial axiom to obtain the final

string of symbols for drawing, and the latter is responsible for

converting a long string of symbols into a list of line segments.

Here is the lsys_build_string function:

def lsys_build_string(lsys, total_iterations):

lstring = lsys.start

for i in range(total_iterations):

output = ''

for symbol in lstring:

if symbol in lsys.rules:

output += lsys.rules[symbol]

else:

output += symbol

lstring = output

return lstring

The lsys_segments_from_string function is a little more complicated

because it has to implement the entire turtle graphics system:

def lsys_segments_from_string(lsys, lstring):

cur_pos = np.array([0., 0.])

cur_angle_deg = 0

cur_state = ( cur_pos, cur_angle_deg )

stack = []

segments = []

for symbol in lstring:

if symbol.isalpha():

if lsys.draw_chars is None or symbol in lsys.draw_chars:

cur_theta = cur_angle_deg * np.pi / 180

offset = np.array([np.cos(cur_theta), np.sin(cur_theta)])

new_pos = cur_pos + offset

segments.append([cur_pos, new_pos])

cur_pos = new_pos

elif symbol == '+':

cur_angle_deg += lsys.turn_angle_deg

elif symbol == '-':

cur_angle_deg -= lsys.turn_angle_deg

elif symbol == '[':

stack.append( ( cur_pos, cur_angle_deg ) )

elif symbol == ']':

cur_pos, cur_angle_deg = stack.pop()

else:

raise RuntimeError('invalid symbol:' + symbol)

return np.array(segments)

The rest of the program is boilerplate including command line argument parsing, defining the benchmark L-Systems, and drawing code.

Overall v0 weighs in at 125 lines of code1 and clocks 7.615 μs per line segment.

v1: Recursion instead of iteration

Whereas v0 uses iterative string replacement, lsystems_v1.py takes a recursive approach to L-System rendering. Instead of explicitly constructing the string of turtle graphics symbols, v1 recursively applies the axiom and replacement rules to implicitly evaluate the string without ever storing it in memory.

The recursive approach is implemented by two functions in v1,

lsys_segments_recursive, and a helper function

_lsys_segments_r. The former sets up some state variables and calls

the latter, and the latter calls itself recursively.

Here is lsys_segments_recursive:

def lsys_segments_recursive(lsys, total_iterations):

cur_pos = np.array([0., 0.])

cur_angle_deg = 0

cur_state = (cur_pos, cur_angle_deg)

state_stack = []

segments = []

s = lsys.start

_lsys_segments_r(lsys, s,

total_iterations,

cur_state,

state_stack,

segments)

return np.array(segments)

As you can see, it initializes the current turtle graphics state, creates an empty stack for saving/restoring state, and hands off the initial axiom string to the helper function.

The helper function calls itself recursively when string replacement

is required, and delegates to another function to execute turtle

graphics commands for each symbol when no replacement is found or the desired number of iterations has

been reached. Here is _lsys_segments_r:

def _lsys_segments_r(lsys, s,

remaining_iterations,

cur_state,

state_stack,

segments):

# for each symbol in input

for symbol in s:

# see if we can run a replacement rule for this symbol

if remaining_iterations > 0 and symbol in lsys.rules:

# get the replacement

replacement = lsys.rules[symbol]

# recursively call this function with fewer remaining steps

cur_state = _lsys_segments_r(lsys, replacement,

remaining_iterations-1,

cur_state,

state_stack, segments)

else: # execute symbol directly

cur_state = _lsys_execute_symbol(lsys, symbol, cur_state,

state_stack, segments)

return cur_state

The _lsys_execute_symbol function called towards the bottom of the

listing implements the same turtle graphics functionality originally

implemented inside of lsys_segments_from_string in v0.

My hope in writing v1 was that it would be faster to avoid allocating and writing strings, since the string itself is just an intermediate representation that is discarded after rendering. Swapping between iteration and recursion often amounts to a tradeoff between heap and stack. Instead of storing data explicitly in heap-allocated strings, the recursive approach stores data implicitly on the call stack. This can be faster, especially when function calls have low overhead.

Unfortunately, I saw a minor slowdown when moving from v0 to v1. Function call complexity varies by language and runtime, both in terms of space (larger stack frames have more storage overhead) and time (how many CPU instructions is a function call in a given language). Interpreted languages like Python often perform worse on both fronts than compiled languages like C, so, my best guess for why v1 is slower than v0 is that the savings in heap allocations/reads/writes is overwhelmed by the additional function call overhead imposed by Python.

In the end, v1 is 172 lines of code and runs at 8.843 μs per segment, just a bit slower than v0.

Since the recursive method in Python was a bit of a dead end, let’s try moving to C!

v2: Porting to C99

My lsystems_v2.c program is a reasonably faithful port of the original v0 string-based code from Python to C99. Since C has no built-in strings or dynamically-sized containers, the first order of business is implementing a typical dynamic array struct that uses malloc, realloc, and free to manage memory. Amortized O(1) array growth is accomplished by doubling storage capacity each time the container needs to expand.

// dynamic array data type

typedef struct darray {

size_t elem_size;

size_t capacity;

size_t count;

unsigned char* data;

} darray_t;

// dynamic array functions

void darray_create(darray_t* darray, size_t elem_size, size_t capacity);

void darray_resize(darray_t* darray, size_t new_count);

void darray_extend(darray_t* darray, const void* elements, size_t count);

void darray_push_back(darray_t* darray, const void* elem);

void darray_pop_back(darray_t* darray, void* elem);

void* darray_elem_ptr(darray_t* darray, size_t idx);

const void* darray_const_elem_ptr(const darray_t* darray, size_t idx);

void darray_get(const darray_t* darray, size_t idx, void* dst);

void darray_set(darray_t* darray, size_t idx, const void* src);

void darray_clear(darray_t* darray);

void darray_destroy(darray_t* darray);

In v2, string building uses a pair of dynamic char arrays in a

double-buffered

fashion to repeatedly apply string replacement. Here is the C version

of lsys_build_string:

char* lsys_build_string(const lsys_t* lsys, size_t total_iterations) {

darray_t string_darrays[2];

for (int i=0; i<2; ++i) {

darray_create(string_darrays + i, sizeof(char),

LSYS_INIT_STRING_CAPACITY);

}

int cur_idx = 0;

darray_extend(string_darrays + cur_idx,

lsys->start,

strlen(lsys->start));

for (int i=0; i<total_iterations; ++i) {

int next_idx = 1 - cur_idx;

darray_t* src_darray = string_darrays + cur_idx;

darray_t* dst_darray = string_darrays + next_idx;

darray_clear(dst_darray);

const char* start = (const char*)src_darray->data;

const char* end = start + src_darray->count;

for (const char* c=start; c!=end; ++c) {

const lsys_sized_string_t* rule = lsys->rules + (int)*c;

if (rule->replacement) {

darray_extend(dst_darray, rule->replacement, rule->length);

} else {

darray_push_back(dst_darray, c);

}

}

cur_idx = next_idx;

}

darray_destroy(string_darrays + (1 - cur_idx));

const char nul = '\0';

darray_push_back(string_darrays + cur_idx, &nul);

return (char*)string_darrays[cur_idx].data;

}

The C version of lsys_segments_from_string sets up a graphics state

stack and calls _lsys_execute_symbol for each symbol in the

string. As in the Python v2 program, the latter function handles the

turtle graphics commands and the state stack. Here is its source code:

void _lsys_execute_symbol(const lsys_t* lsys,

const char symbol,

darray_t* segments,

lsys_state_t* state,

darray_t* state_stack) {

if (isalpha(symbol)) {

if (lsys->draw_chars[0] && !lsys->draw_chars[(int)symbol]) {

return;

}

float c = cosf(state->angle);

float s = sinf(state->angle);

float xnew = state->pos.x + c;

float ynew = state->pos.y + s;

lsys_segment_t seg = { { state->pos.x, state->pos.y},

{ xnew, ynew } };

darray_push_back(segments, &seg);

state->pos.x = xnew;

state->pos.y = ynew;

} else if (symbol == '+' || symbol == '-') {

float delta = ( (symbol == '+') ?

lsys->turn_angle_rad : -lsys->turn_angle_rad );

state->angle += delta;

} else if (symbol == '[') {

darray_push_back(state_stack, state);

} else if (symbol == ']') {

darray_pop_back(state_stack, state);

} else {

fprintf(stderr, "invalid character in string: %c\n", symbol);

exit(1);

}

}

The rest of the program is concerned with getting to the point where it can call lsys_build_string and lsys_segments_from_string, and writing out the segments to a text file for later plotting (note that output time is not included in the benchmarks).

In writing this program (and subsequent C versions), I tried to adopt many of the conventions from Andre Weissflog’s useful blog post Modern C for C++ Peeps. For instance, I use C99-style anonymous struct arrays when initializing the known L-Systems:

typedef struct lsys_rule_def {

char symbol;

const char* replacement;

} lsys_rule_def_t;

void lsys_create(lsys_t* lsys,

const char* name,

const char* start,

lsys_rule_def_t const rules[],

double turn_angle_deg,

const char* draw_chars);

void initialize_known_lsystems(void) {

lsys_create(KNOWN_LSYSTEMS + LSYS_SIERPINSKI_TRIANGLE,

"sierpinski_triangle", "F-G-G",

(lsys_rule_def_t[]){

{ 'F', "F-G+F+G-F" },

{ 'G', "GG" },

{ 0, 0 }

}, 120, NULL);

// etc...

}

Of course C code is less pithy than Python, especially when implementing our own data types like the dynamically resized array. Unsurprisingly v2 is over 3x larger than v0, at 404 lines compared to 125. However, the increase in throughput is over 100x: 68.62 nanoseconds per segment for v2, versus 7.615 microseconds per segment for v0.

While impressive, this type of speedup is fairly typical when porting code from Python to C – although packages like Cython, Numba, and pypy are all narrowing the gap.

v3: Recursive approach in C

Hopeful that function calls would incur less overhead in C than in Python, I once again implemented the recursive approach in lsystems_v3.c. Again, the goal is to trade off explicit heap allocation for implicit storage on the call stack, thereby avoiding some unnecessary heap allocations, reads, and writes.

Here’s the C analog to v1’s _lsys_segments_r recursive function, almost

exactly the same as the Python version:

void _lsys_segments_r(const lsys_t* lsys,

const char* lstring,

size_t remaining_iterations,

darray_t* segments,

lsys_state_t* cur_state,

darray_t* state_stack) {

for (const char* psymbol=lstring; *psymbol; ++psymbol) {

int symbol = *psymbol;

const lsys_sized_string_t* rule = lsys->rules + symbol;

if (remaining_iterations && rule->replacement) {

_lsys_segments_r(lsys, rule->replacement,

remaining_iterations-1,

segments, cur_state, state_stack);

} else {

_lsys_execute_symbol(lsys, *psymbol, segments,

cur_state, state_stack);

}

}

}

The wrapper function that calls it also looks pretty similar to the Python v1, albeit with some explicit memory management:

darray_t* lsys_segments_recursive(const lsys_t* lsys,

size_t total_iterations) {

darray_t* segments = malloc(sizeof(darray_t));

darray_create(segments, sizeof(lsys_segment_t),

LSYS_INIT_SEGMENTS_CAPACITY);

darray_t state_stack;

darray_create(&state_stack, sizeof(lsys_state_t),

LSYS_INIT_STATES_CAPACITY);

lsys_state_t cur_state = LSYS_START_STATE;

_lsys_segments_r(lsys, lsys->start,

total_iterations, segments,

&cur_state, &state_stack);

darray_destroy(&state_stack);

return segments;

}

Adding recursion to v3 costs a few lines of code, growing the program to 457 lines from v2’s 404 lines. So, what’s the big payoff? A whopping 8% increase in throughput! The time per segment goes down, but only just barely to 63.45 ns per segment, versus v2’s 68.62 ns per segment.

Very underwhelming.

I guess the heap strategy really isn’t as bad as I initially imagined, despite the fact that the intermediate string representation is built and then discarded. Upon further reflection, I wonder whether the string building method benefits from increased cache coherence over the recursive method, since the only things that need to be in memory during string building are the source string, the output string, and the L-System replacement rules.

In the end, the recursive method is still a little bit faster, and the code is already written, so let’s just keep going with this approach and see where it takes us…

v4: Attempting to cache cos/sin

The next version,

lsystems_v4.c,

tried to be a little bit clever and reduce the number of calls to

cosf and sinf by storing the cosine and sine of the current angle

in the graphics state struct.

Let’s inspect changes to the source code of

_lsys_execute_symbol. Here’s v3 handling turn symbols + and -:

state->angle += delta;

…compare with v4:

state->angle += delta;

state->rot.c = cosf(state->angle);

state->rot.s = sinf(state->angle);

How v3 computes new segment coordinates:

float c = cosf(state->angle);

float s = sinf(state->angle);

float xnew = state->pos.x + c;

float ynew = state->pos.y + s;

Compare with the v4 version:

float xnew = state->pos.x + state->rot.c;

float ynew = state->pos.y + state->rot.s;

The v4 program weighs in at 461 lines of code and clocks at 64.94 ns per segment – not a really significant changes from v3 in either metric.

v5: Precomputing all rotations

I decided to run a little further with reducing calls to cosf and

sinf. Since all of the L-Systems in the benchmark set have a integer

turning angles, with enough rotations each one will eventually get

back to the initial angle of 0°.

For example, the Sierpinski arrowhead L-System with its angle increment of 60° system cycles every six turns, because 6 × 60° = 360°, a full rotation.

As a more complex example, the angle increment for the Barnsley fern L-System is 25°, which does not evenly divide 360°. However, after 72 turns, the Barnsley fern L-System reaches 1,800° which is equivalent to five full rotations, so we can say this angle increment has a cycle length of 72.

With that in mind, lsystems_v5.c precomputes the cosine and sine of every possible turning angle for an L-System up to its maximum cycle length at program start-up. For L-Systems that have short (i.e. up to length 256) cycles, the graphics state no longer holds the system’s angle in radians – instead it holds the integer number of turns into the cycle. As with v4, the graphics state also stores the cosine and sine of the current angle, however these are now pulled from a lookup table when turns occur.

Here’s the new code in _lsys_execute_symbol for handling + and -:

if (lsys->rotation_cycle_length) { // we have precomputed cos/sin

int delta = (symbol == '+') ? 1 : -1;

int t = positive_mod((int)state->angle + delta,

lsys->rotation_cycle_length);

state->angle = t;

state->rot = lsys->rotations[t];

} else { // no precomputed cos/sin, just compute here

float delta = ( (symbol == '+') ?

lsys->turn_angle_rad : -lsys->turn_angle_rad );

state->angle += delta;

state->rot.c = cosf(state->angle);

state->rot.s = sinf(state->angle);

}

This small amount of precomputation delivers a big increase in performance: v5 is down to 29.64 ns per segment (over 2x faster than v3 and v4), and weighs in at 499 lines of code.

For those keeping score at home, we are now over 250x faster than the initial Python version. But hey, let’s keep going!

v6: Memoizing replacements

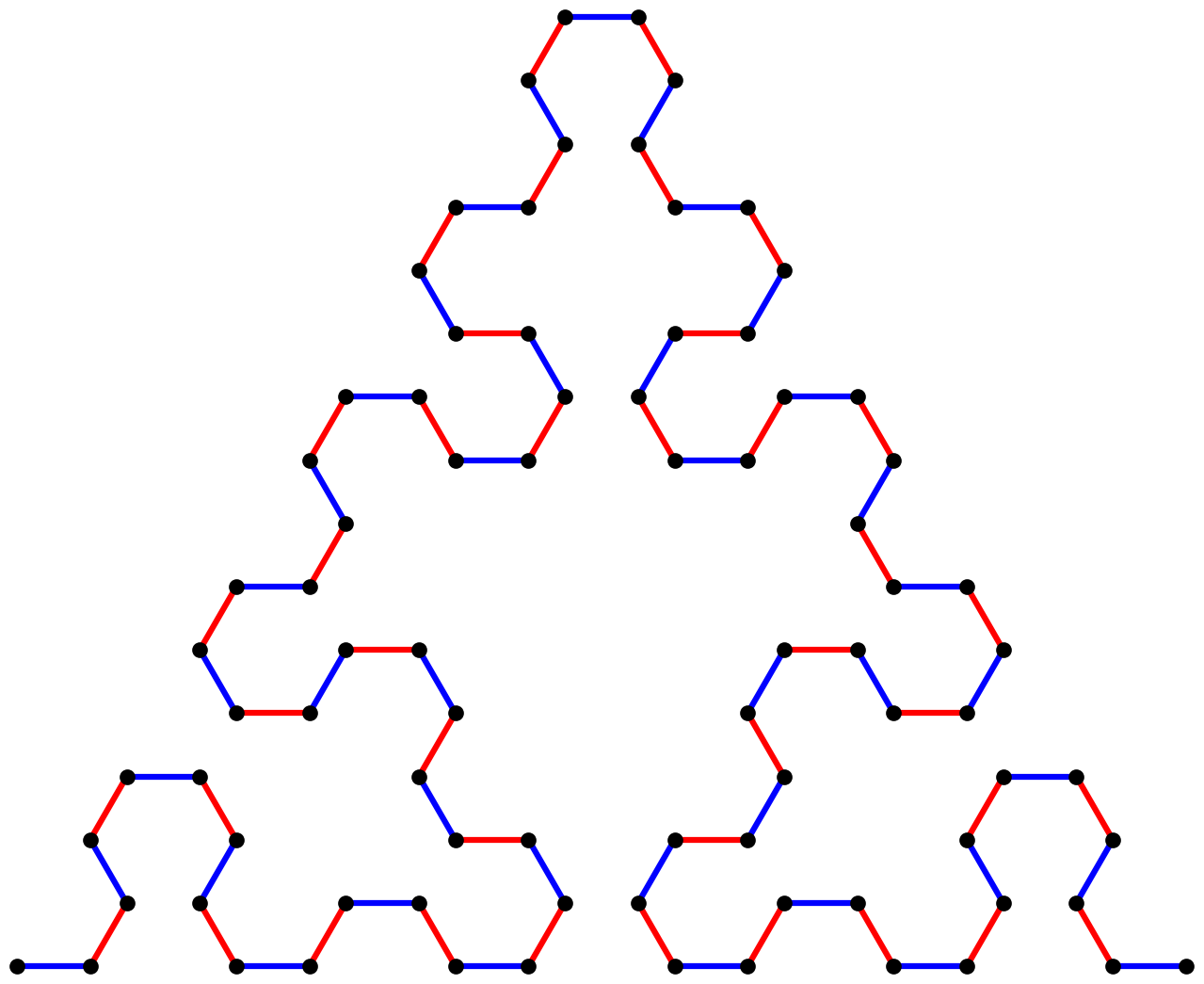

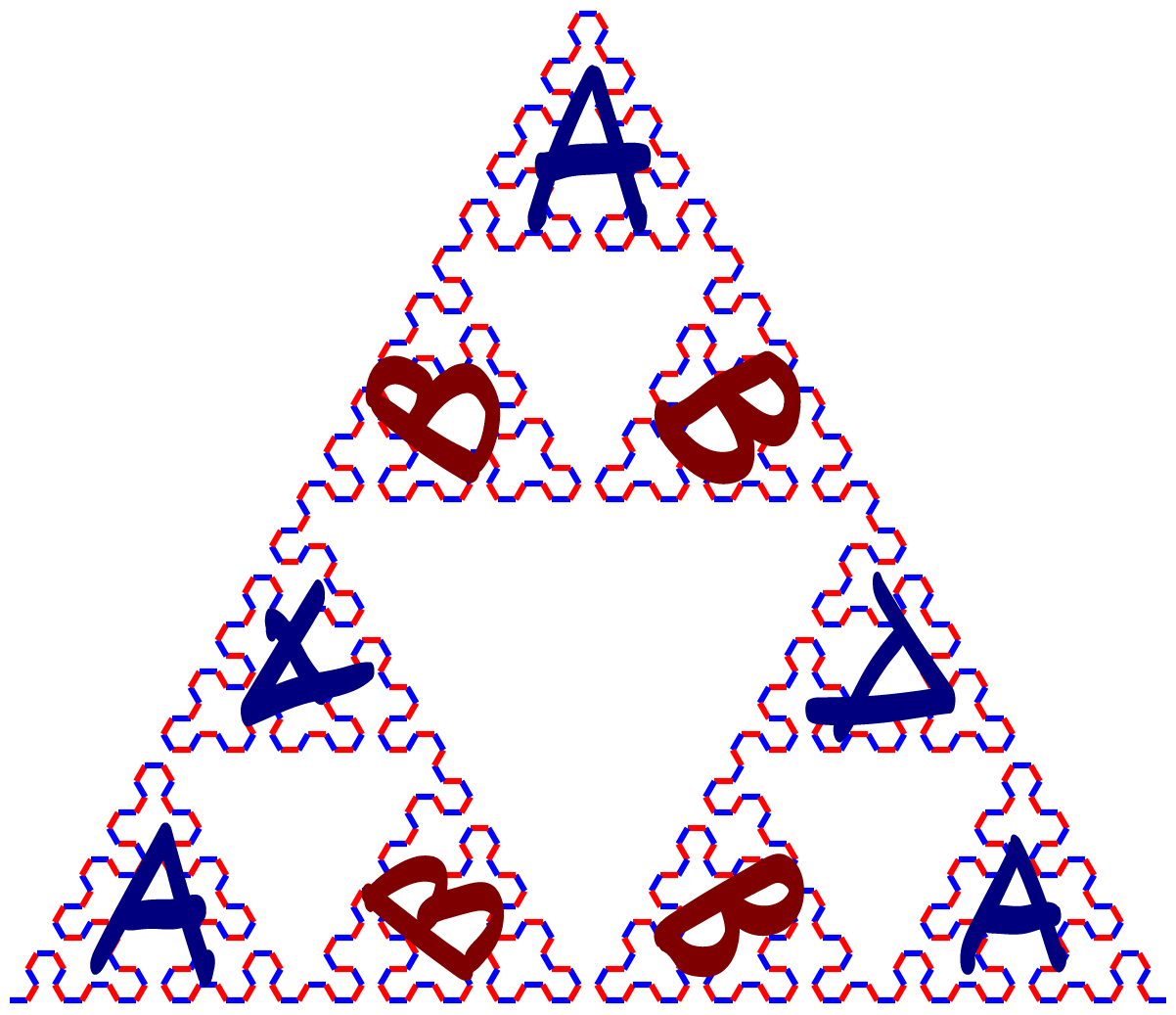

Let’s once again consider the Sierpinski arrowhead system at iteration six:

If you look carefully, you can find five rotated and translated copies

of the iteration-four Sierpinski arrowhead in the above figure,

obtained by starting with the axiom A and applying the replacement

rules four times. It looks like this:

There are also four copies of the figure obtained by starting with the

axiom B and applying the replacement rules to a depth of four:

Let’s label the nine copies of these figures in the original iteration-six image:

Since each all of the A components in the image above are identical,

up to differing positions and orientations (and same for the B

components), why not re-use the computation that produced them?

This is the crux of the motivation for

lsystems_v6.c.

The goal here is basically to implement memoization – remembering which segments are produced when a given replacement rule is invoked for a particular number of iterations, so that the next time the rule is invoked at the same iteration count, the renderer can just “play them back” at the correct position and orientation.

Here is the new _lsys_segments_r function that handles recursion and

memoization. It depends on a few functions to handle 2D rigid

transformations that I also introduced in v6.

void _lsys_segments_r(const lsys_t* lsys,

const char* lstring,

size_t remaining_iterations,

darray_t* segments,

xform_t* cur_state,

darray_t* xform_stack,

lsys_memo_set_t* mset) {

// for each symbol in input string

for (const char* psymbol=lstring; *psymbol; ++psymbol) {

int symbol = *psymbol;

const lsys_sized_string_t* rule = lsys->rules + symbol;

// see if we should invoke a replacement rule

if (remaining_iterations && rule->replacement) {

// remember # of segments emitted so far and graphics state

size_t segment_start = segments->count;

xform_t xform_start = *cur_state;

if (mset) { // if memoization turned on

// see if we have already memoized this symbol

lsys_memo_t* memo = mset->memos[symbol];

// if so, and if we are at the correct iter. count to playback

if (memo && memo->memo_iterations == remaining_iterations) {

// time to play back a memoized recording!

// create a relative transformation to deal with

// change in graphics state since original recording

xform_t update_xform =

xform_compose(*cur_state, memo->init_inverse);

// resize the output array so we can write to each index

darray_resize(segments,

segment_start + memo->segment_count);

// pointer to start of recording in output array

const lsys_segment_t* src =

darray_const_elem_ptr(segments, memo->segment_start);

// pointer to where we will place output

lsys_segment_t* dst =

darray_elem_ptr(segments, segment_start);

// for each segment in recording, transform and store it

for (size_t i=0; i<memo->segment_count; ++i) {

lsys_segment_t newsrc = {

xform_transform_point(update_xform, src[i].p0),

xform_transform_point(update_xform, src[i].p1)

};

dst[i] = newsrc;

}

// update the current graphics state

*cur_state = xform_compose(*cur_state, memo->delta_xform);

// done with the current symbol

continue;

}

} // memoization not available or wrong iter. count to playback

// recursive call on replacement for current symbol

_lsys_segments_r(lsys, rule->replacement,

remaining_iterations-1,

segments, cur_state, xform_stack,

mset);

// if memoization turned on and this symbol not yet memoized

if (mset && !mset->memos[symbol]) {

// see how many segments were emitted by the recursive call

size_t segment_count = segments->count - segment_start;

// if it was a large enough batch of segments or we are

// at the maximum iter. count to get a reasonable payoff

if (segment_count > mset->min_memo_segments ||

remaining_iterations == mset->total_iterations - 2) {

// time to memoize the segments that were

// just emitted by the recursive call

// allocate a new memoization struct

lsys_memo_t* new_memo = malloc(sizeof(lsys_memo_t));

// store the necessary info

new_memo->memo_iterations = remaining_iterations;

new_memo->segment_start = segment_start;

new_memo->segment_count = segment_count;

new_memo->init_inverse = xform_inverse(xform_start);

new_memo->delta_xform = xform_compose(

new_memo->init_inverse, *cur_state);

// add it to our array of memoized symbols

mset->memos[symbol] = new_memo;

}

}

} else {

// no replacement rule available or zero iterations remaining

// just directly execute symbol

_lsys_execute_symbol(lsys, *psymbol, segments,

cur_state, xform_stack);

}

}

}

The tricky part of this is figuring out the right time to memoize. Memoizing too small of a run of segments is a performance drag because of the overhead of setting up the recording, and too large may not realize a great deal of savings either, because the segments needed to be computed in full on the first run-through.

I introduced a parameter min_memo_segments to regulate this

behavior. The first time the a recursive call to _lsys_segments_r

results in at least min_memo_segments being appended to the output

array, subsequent calls to _lsys_segments_r for the same symbol /

iteration count computation will play back the previous computation.

Implementing memoization caused a substantial increase in program size – v6 is 628 lines of code compared with 499 in v5. However, there’s a very respectable performance increase, as v6 achieves 9.583 ns per segment versus 29.64 ns per segment for v5 – over a 3x speedup!

But we have one more trick up our sleeve…

v7: Parallelized memo playback

Although I didn’t see a straightforward way to parallelize the string

method, there was one loop in the memoization playback function above

that was crying out for a #pragma omp parallel for.

I added OpenMP parallelization to memoization playback in lsystems_v7.c, which gave a nice little performance boost. Here’s the relevant change:

int do_parallelize =

(memo->segment_count >= mset->min_parallel_segments);

#pragma omp parallel for if (do_parallelize)

for (size_t i=0; i<memo->segment_count; ++i) {

lsys_segment_t newsrc = {

xform_transform_point(update_xform, src[i].p0),

xform_transform_point(update_xform, src[i].p1)

};

dst[i] = newsrc;

}

Again, we make sure there is some benefit to parallelization by avoiding thread startup overhead for small runs of segments.

The final v7 version is 660 lines of code and runs at 6.073 ns per segment, over 1200x faster than the original Python version, while weighing in at less than 6x the size.

Results

Benchmarks were run on my 2013 MacBook Pro with a 2.8 GHz Intel Core i7. The installed Python configuration is

Python 3.7.7 (default, Mar 18 2020, 09:44:23)

[Clang 9.1.0 (clang-902.0.39.2)]

C programs were compiled by gcc 8, configured as

Using built-in specs.

COLLECT_GCC=gcc-mp-8

COLLECT_LTO_WRAPPER=/opt/local/libexec/gcc/x86_64-apple-darwin17/8.4.0/lto-wrapper

Target: x86_64-apple-darwin17

Configured with: /opt/local/var/macports/build/_opt_bblocal_var_buildworker_ports_build_ports_lang_gcc8/gcc8/work/gcc-8.4.0/configure --prefix=/opt/local --build=x86_64-apple-darwin17 --enable-languages=c,c++,objc,obj-c++,lto,fortran --libdir=/opt/local/lib/gcc8 --includedir=/opt/local/include/gcc8 --infodir=/opt/local/share/info --mandir=/opt/local/share/man --datarootdir=/opt/local/share/gcc-8 --with-local-prefix=/opt/local --with-system-zlib --disable-nls --program-suffix=-mp-8 --with-gxx-include-dir=/opt/local/include/gcc8/c++/ --with-gmp=/opt/local --with-mpfr=/opt/local --with-mpc=/opt/local --with-isl=/opt/local --enable-stage1-checking --disable-multilib --enable-lto --enable-libstdcxx-time --with-build-config=bootstrap-debug --with-as=/opt/local/bin/as --with-ld=/opt/local/bin/ld --with-ar=/opt/local/bin/ar --with-bugurl=https://trac.macports.org/newticket --disable-tls --with-pkgversion='MacPorts gcc8 8.4.0_0'

Thread model: posix

gcc version 8.4.0 (MacPorts gcc8 8.4.0_0)

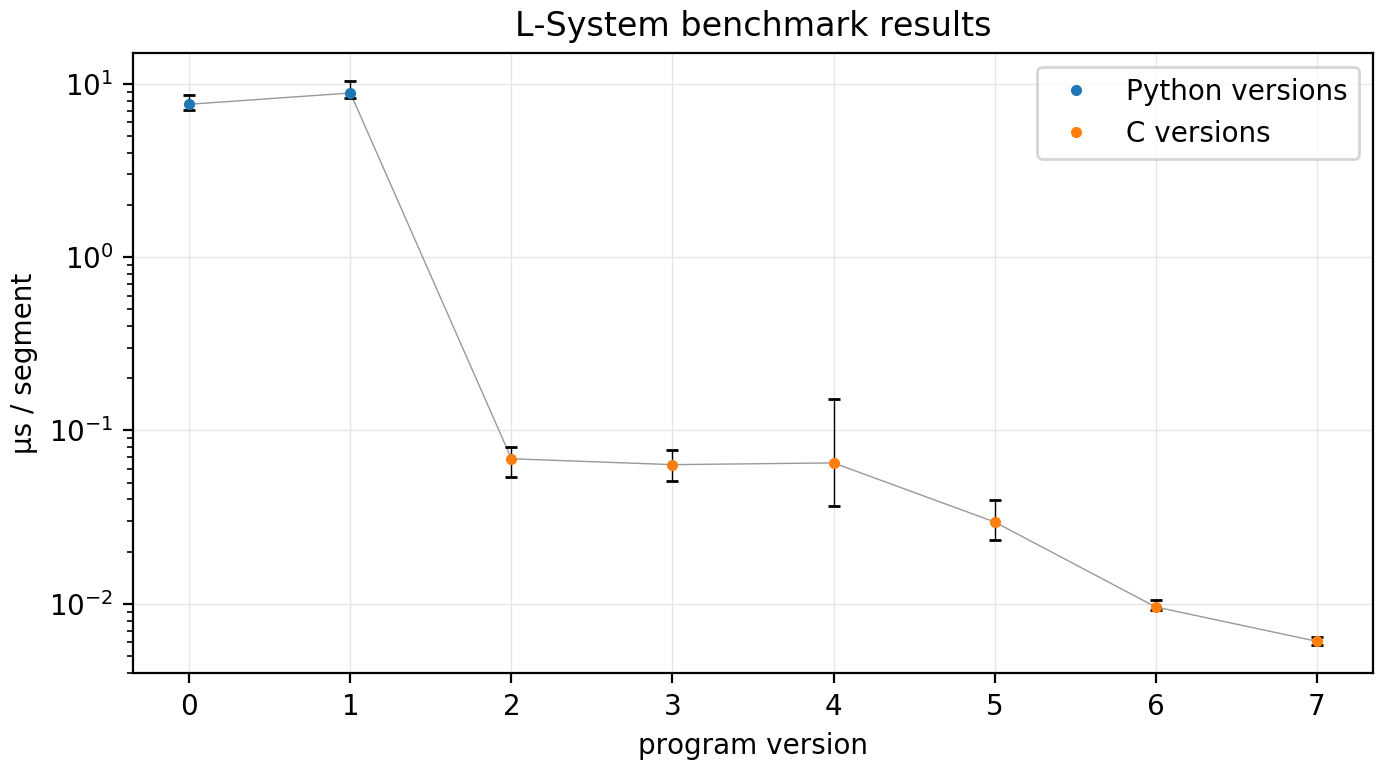

The plot below shows timing results for all program versions. Note the log scale on the y-axis. The error bars denote the full range (min and max) of observed timings on each benchmark L-System listed in the appendix below, and the central point is computed as the geometric mean of all benchmark L-Systems for each program version.

The various versions of the program and their notable features are summarized in the table below, with links to each section above where they are discussed.

| Version | Language | String | Recursive | SLOC1 | Time/segment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| v0 | Python | ✓ | 125 | 7.615 μs | Initial Python version | |

| v1 | Python | ✓ | 172 | 8.843 μs | Added recursion | |

| v2 | C | ✓ | 404 | 68.62 ns | Initial C version | |

| v3 | C | ✓ | 457 | 63.45 ns | Added recursion | |

| v4 | C | ✓ | 461 | 64.94 ns | Cache trigonometry | |

| v5 | C | ✓ | 499 | 29.64 ns | Precompute all rotations | |

| v6 | C | ✓ | 628 | 9.583 ns | Memoization | |

| v7 | C | ✓ | 660 | 6.073 ns | OpenMP parallelization |

Full source code for each version is available in the github repository.

Conclusions

This project was a fun diversion to geek out on while normal life seems to be on pause. It reminded me in some ways of my business card raytracer project – fussing around with small changes version by version until I was satisfied.

One interesting lesson for me was that optimizations which seemed to be initially ineffective – i.e. storing cosines/sines in the state, and recursion vs iterative string replacement – ended up leading to giant payoffs. For the former, it was realizing I could precompute all possible rotation angles, and the latter directly enabled a 3x speedup due to memoization.

Of course there are many ways I could imagine taking this further, including all of the proscribed techniques I listed at the very top. If I wanted to try to outperform GCC’s own vectorization, I could try my hand at writing my own SIMD to transform vertices during playback. Or going one step further, I could get a boost by doing transformation & playback on the GPU (although I’d wonder about memory transfer overhead back to system RAM). And similar to old-school compiled sprites, just-in-time generation of x86_64 code specific to each L-System could definitely increase throughput. But I don’t want to get into the compiler business just yet, I think.

Short of these things, I’ve applied all of the big optimizations I can think of. But if you think I missed any, or if you have any questions or comments on this post, chime in on this twitter thread.

Thanks for reading!

Appendix: all L-Systems for benchmark

I cherry-picked a few choice examples of L-Systems from the Wikipedia page linked above as well as Paul Bourke’s page on L-Systems. The systems listed below were used to benchmark all of the various program versions described in this post.

Each L-System was run to a different number of iterations by the code, with the goal of limiting each program’s runtime to approximately 1-10 seconds. Therefore, the C programs were given a much larger iteration count than their Python counterparts.

The table below summarizes the iteration counts and number of output line segments for each benchmark L-System.

| L-System | Python iterations | Python segments | C iterations | C segments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sierpinski arrowhead | 12 | 531,441 | 17 | 129,140,163 |

| Sierpinski triangle | 11 | 531,441 | 16 | 129,140,163 |

| Dragon curve | 18 | 524,288 | 26 | 134,217,728 |

| Barnsley fern | 9 | 654,592 | 13 | 167,759,872 |

| Sticks | 11 | 350,198 | 16 | 85,962,370 |

| Hilbert curve | 9 | 262,143 | 13 | 67,108,863 |

| Pentaplexity | 6 | 233,280 | 9 | 50,388,480 |

See below for rule sets and example renderings of each benchmark L-System.

Sierpinski arrowhead

- Axiom:

A - Angle increment: 60°

- Rules:

A→B-A-BB→A+B+A

Rendering of iteration 7:

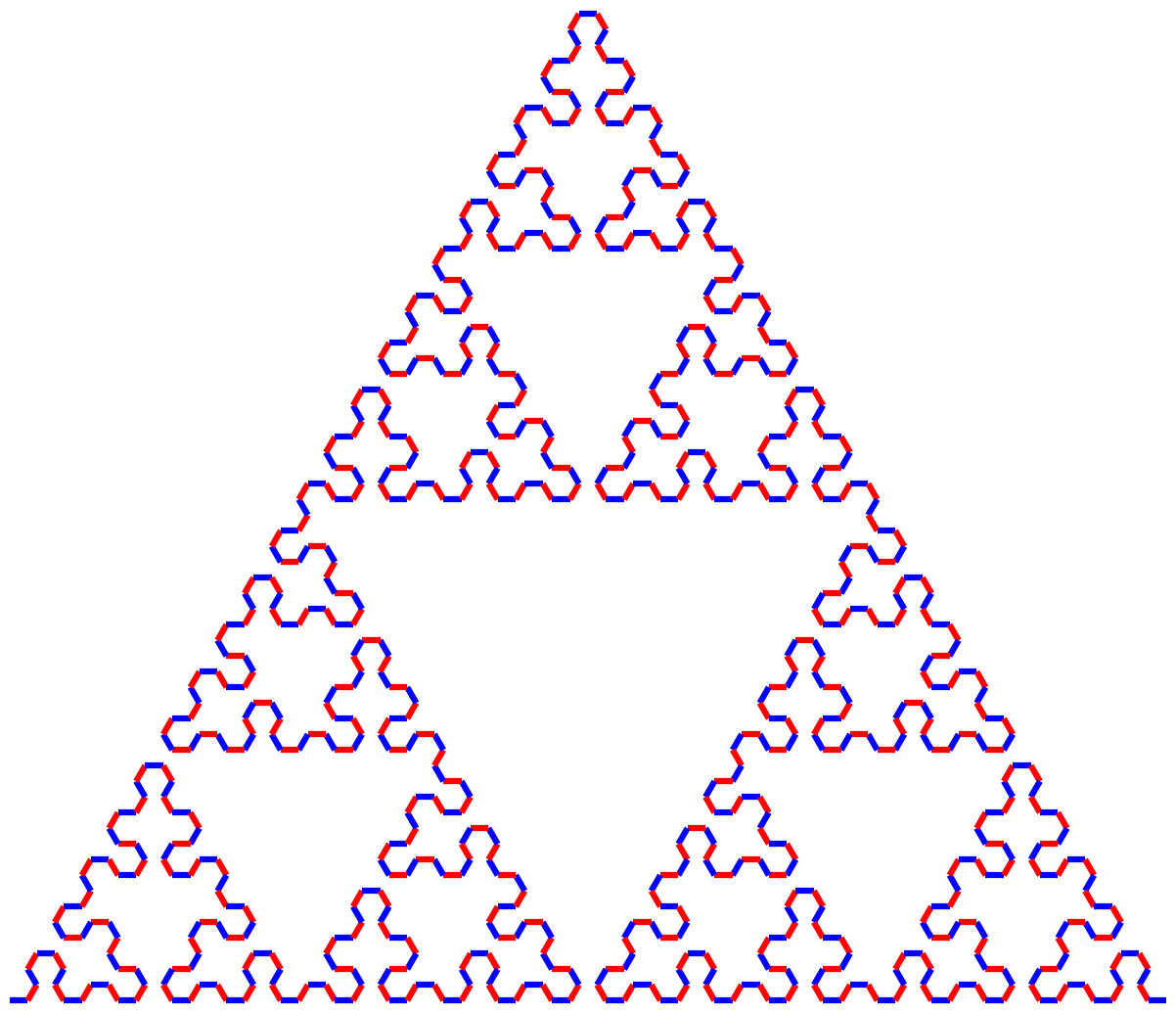

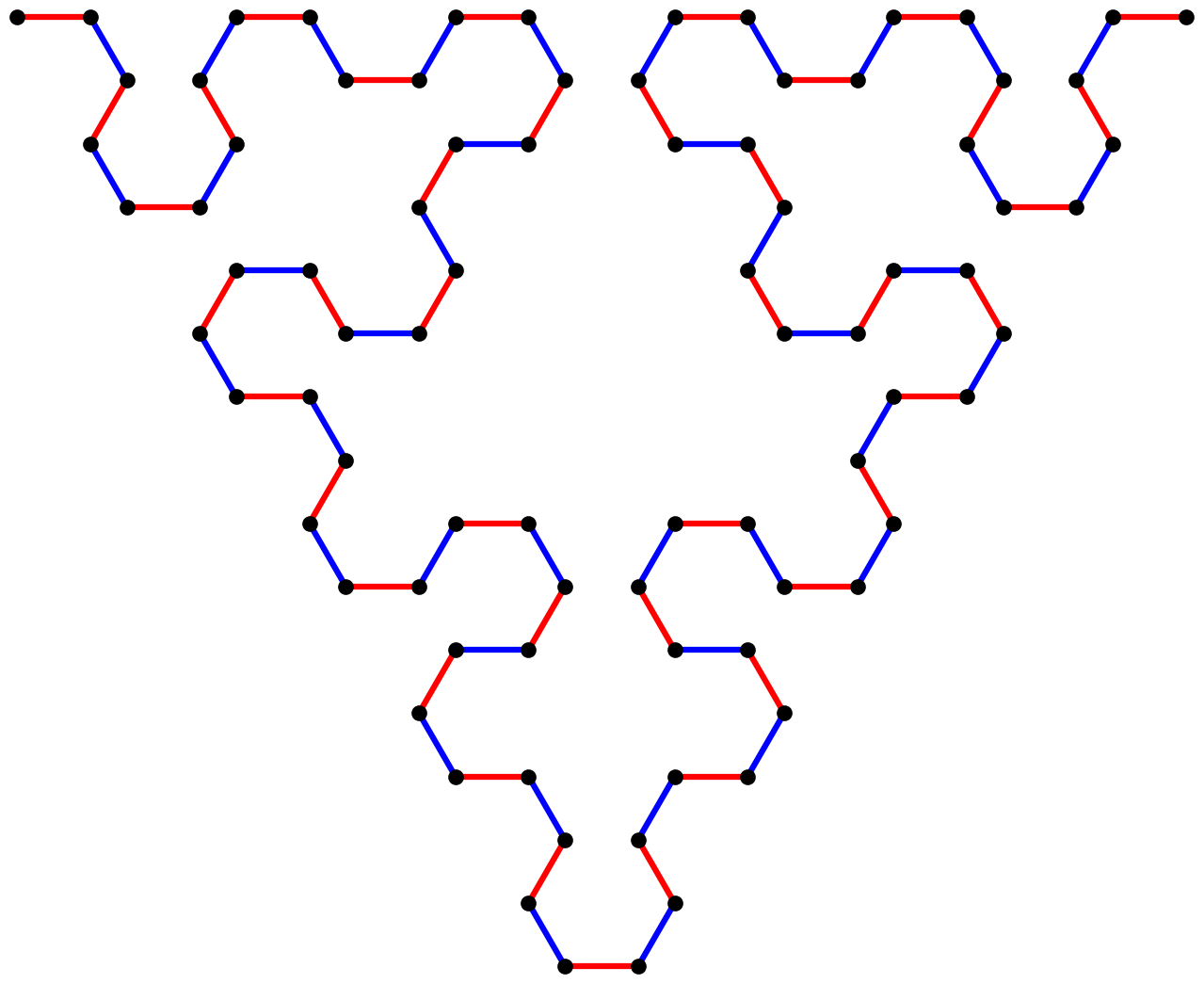

Sierpinski triangle

- Axiom:

F-G-G - Angle increment: 120°

- Rules:

F→F-G+F+G-FG→GG

Rendering of iteration 6:

Dragon curve

- Axiom:

FX - Angle increment: 90°

- Rules:

X→X+YF+Y→-FX-Y

Rendering of iteration 12:

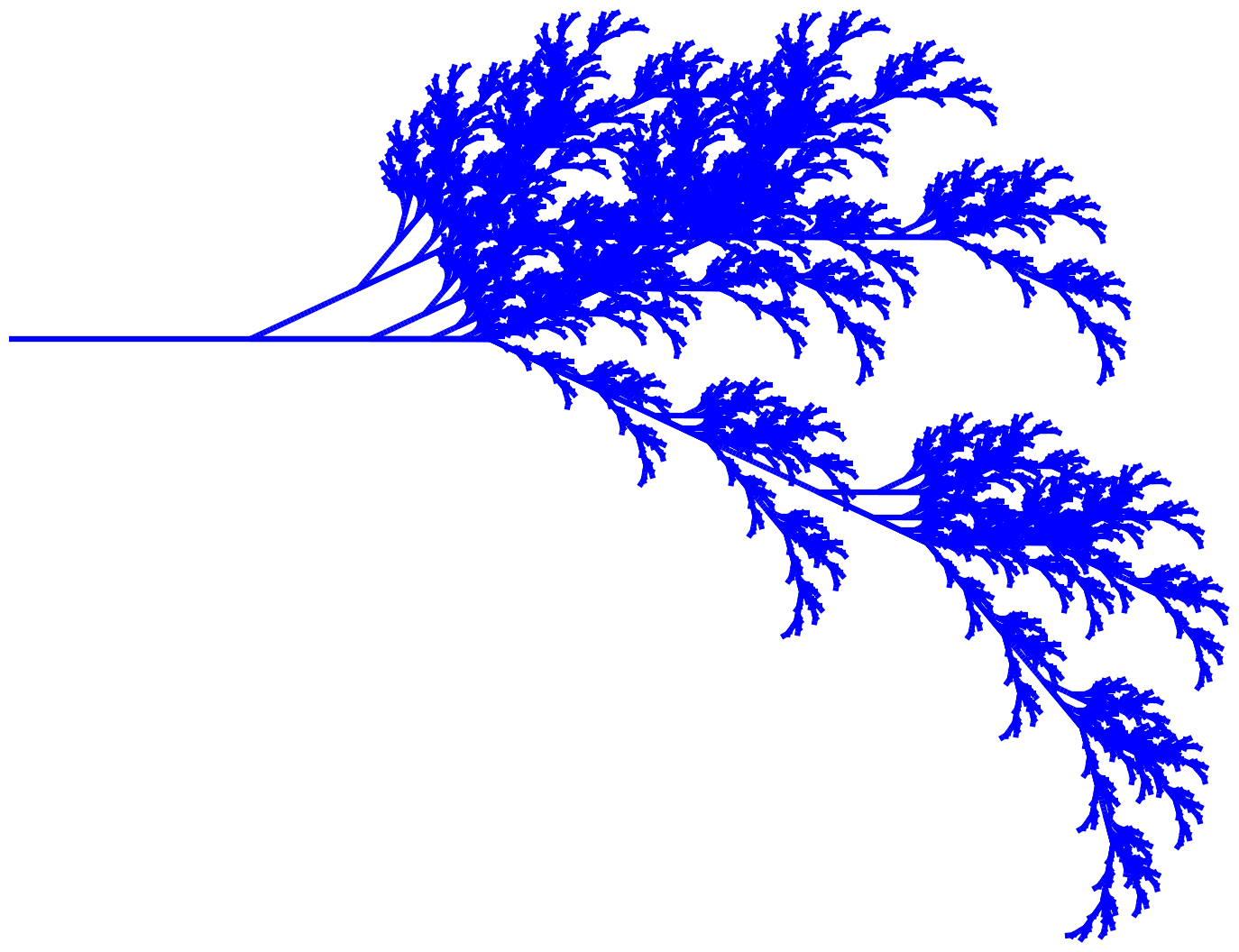

Barnsley fern

- Axiom:

X - Angle increment: 25°

- Rules:

X→F+[[X]-X]-F[-FX]+XF→FF

Rendering of iteration 7:

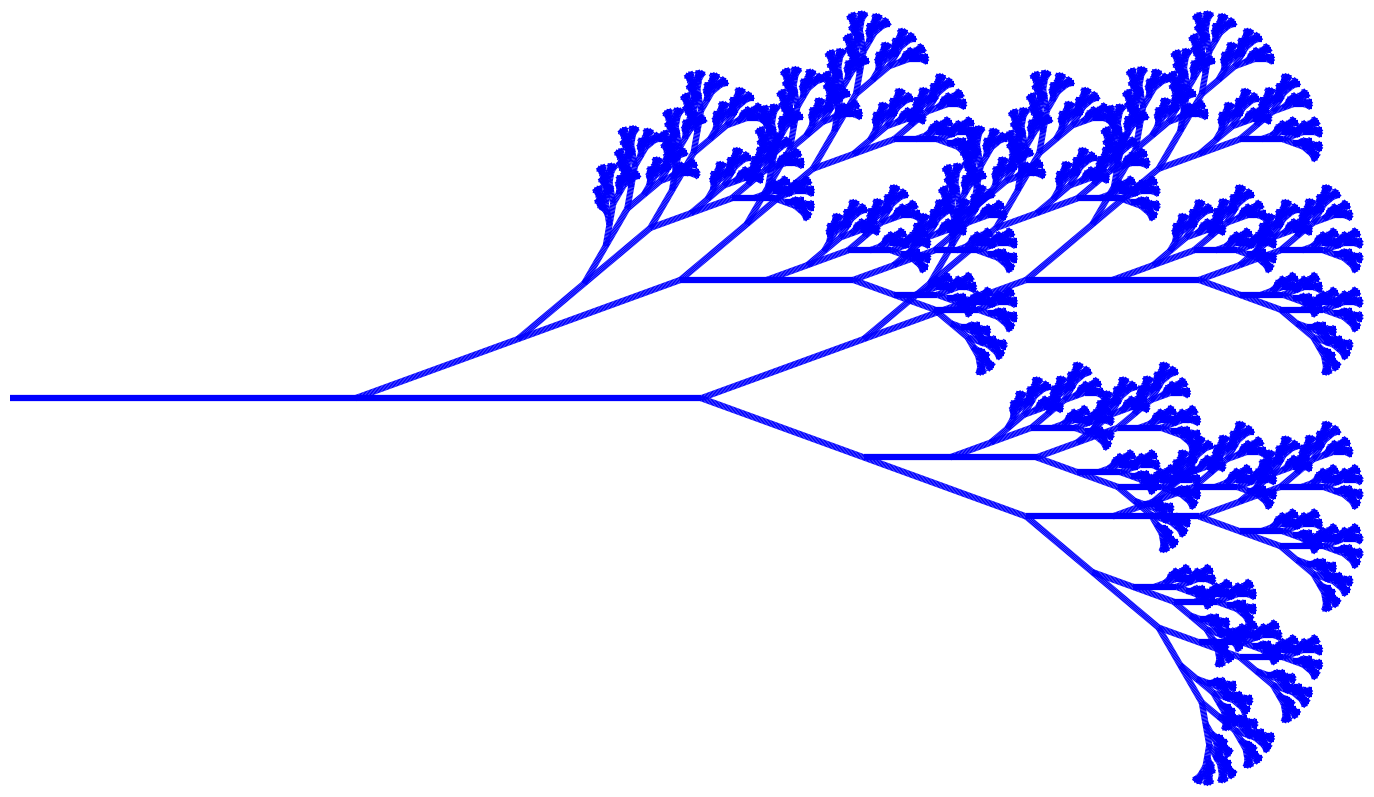

Sticks

- Axiom:

X - Angle increment: 20°

- Rules:

X→F[+X]F[-X]+XF→FF

- Note: only draw segments for

F

Rendering of iteration 9:

Hilbert curve

- Axiom:

L - Angle increment: 90°

- Rules:

L→+RF-LFL-FR+R→-LF-RFR-FL-

- Note: only draw segments for

F

Rendering of iteration 5:

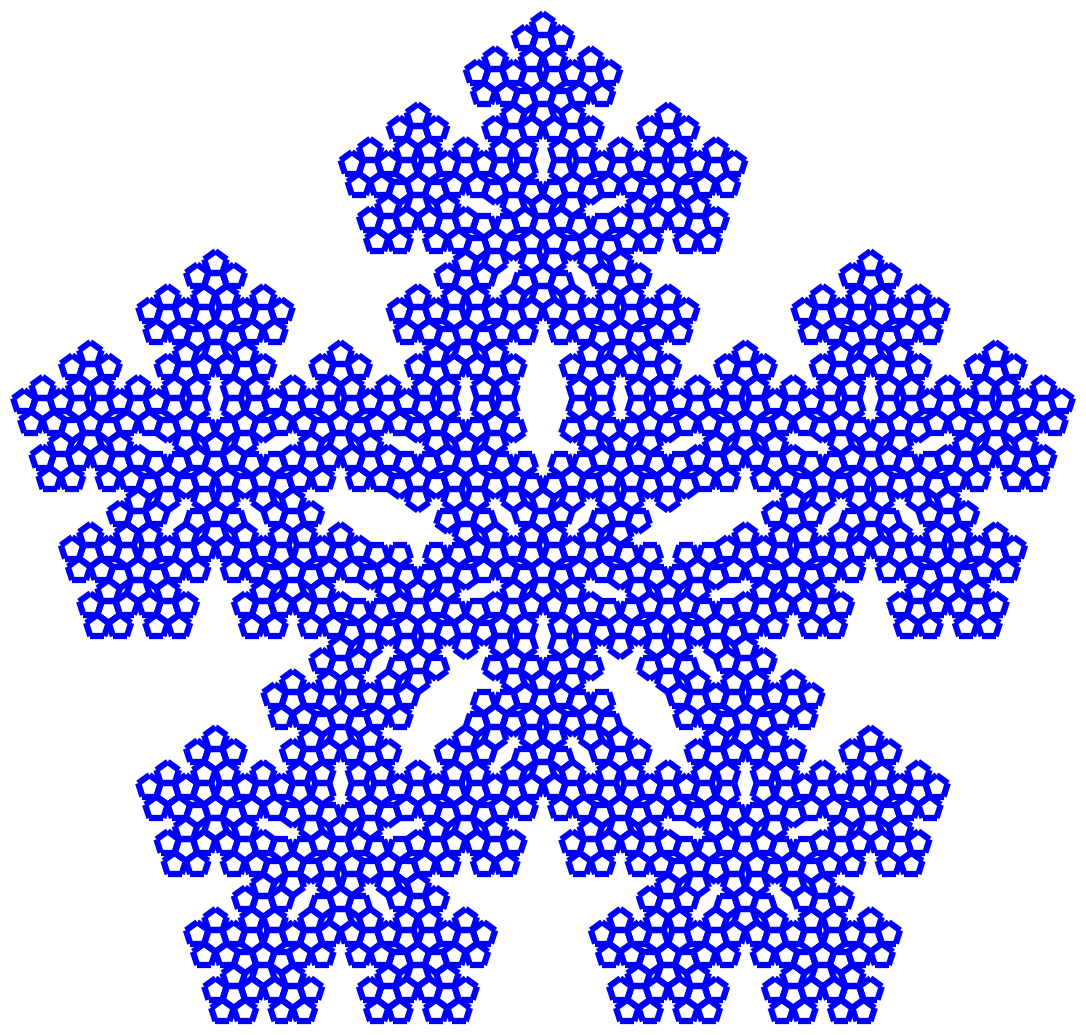

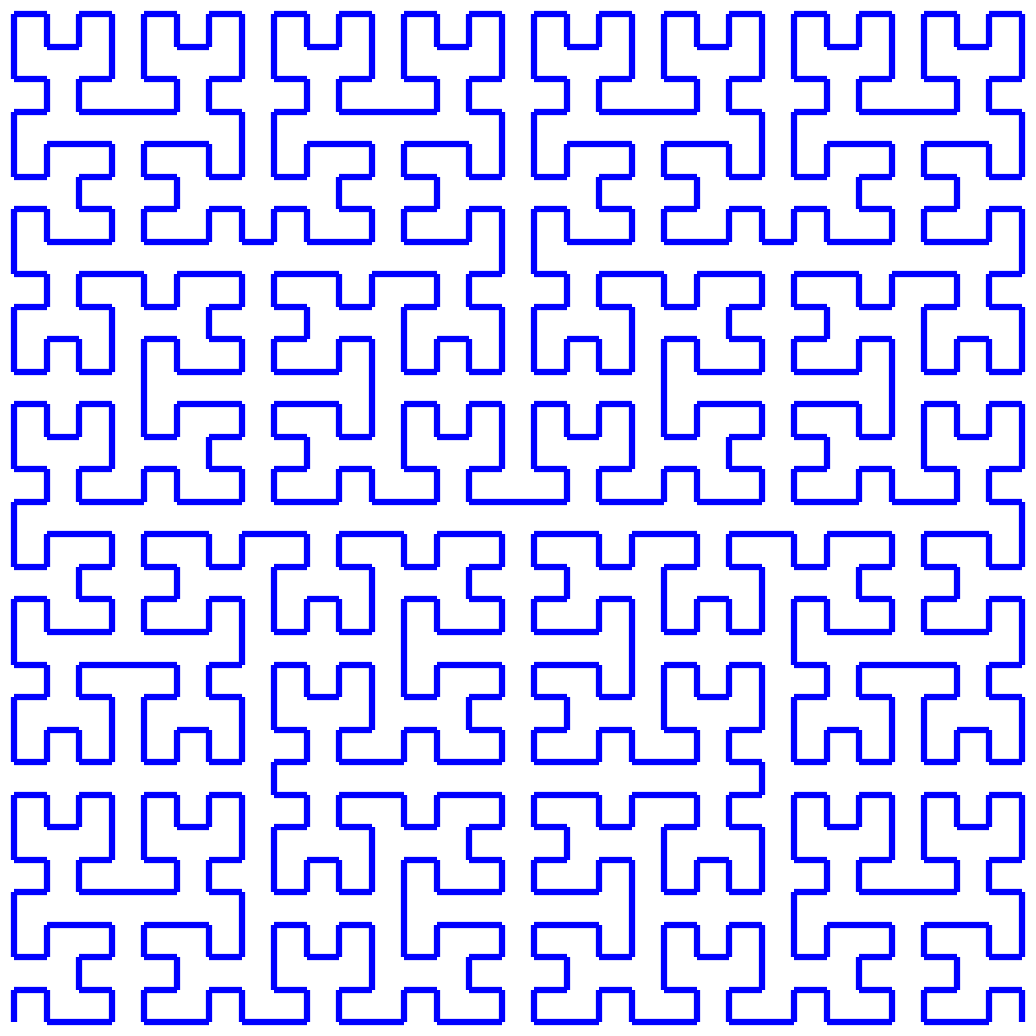

Pentaplexity

- Axiom:

F++F++F++F++F - Angle increment: 36°

- Rules:

F→F++F++F+++++F-F++F

Rendering of iteration 4: